ADA – analog interactive installation/kinetic sculpture/post-digital drawing machine

Similiar to Tinguely’s “Méta-Matics”, “ADA” is an artwork with a soul. It acts itself. At Tinguely’s, it is sufficient to be an unwearily struggling mechanical being. He took it wryly: the machine produces nothing but its industrial self-destruction. Whereas “ADA” by Karina Smigla-Bobinski is a post-industrial “creature”, visitor-animated, creatively acting artist-sculpture, self-forming artwork, resembling a molecular hybrid such as the one from nanobiotechnology. It develops the same rotating silicon-carbon-hybrids, midget tools, miniature machines able to generate simple structures.

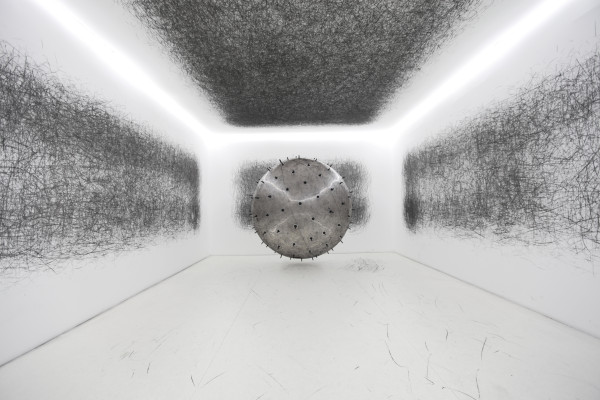

“ADA” is much larger, esthetically much more complex, an interactive art-making machine. Filled up with helium, floating freely in the room, a transparent, membrane-like globe, spiked with charcoals that leave marks on the walls, ceilings and floors. Marks which “ADA” produces quite autonomously, although moved by a visitor. The globe obtains an aura of liveliness and its black coal traces produce the appearance of a drawing. The globe, when put in action, fabricates a composition of lines and points that remain incalculable in their intensity, expression or form, however hard the visitor tries to control “ADA”, to drive her, to domesticate her. Whatever they try out, they notice very soon that “ADA” is an independent performer, studding the originally white walls with drawings and signs. More and more complicated fabric structures arise. This is a movement experienced visually, which, like a computer, makes an unforeseeable output after entering a command. It is not by chance that “ADA” reminds of Ada Lovelace, who in the 19th century, together with Charles Babbage, developed the very first prototype of a computer. Babbage provided the preliminary computing machine, while Lovelace provided the first software. A symbiosis of mathematics with the romantic legacy of her father Lord Byron emerged there. Ada Lovelace intended to create a machine that would be able to create works of art, such as poetry, music or pictures, like an artist does. “ADA” by Karina Smigla-Bobinski follows this very tradition, as well as the one of Vannevar Bush, who built a Memex Machine (Memory Index) in 1930 (“We wanted the memex to behave like the intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain”), or the Jacquard’s loom that needed a punch card in order to weave flowers and leaves; or the “analytic machine” of Babbage which extracted algorithmic patterns.

“ADA” uprose in a contemporary spirit of biotechnology. She is a vital performance-machine, and her patterns of lines and points get more and more complex as the number of the audience playing increases. Leaving traces that cannot be deciphered by neither the artist nor the visitors, let alone by “ADA” herself. And still, “ADA”’s work is unmistakably potentially humane because the only available decoding method for these signs and drawings is the association to which our brain corresponds especially when it sleeps: the truculent jazziness of our dreams.

© ADA – analog interactive installation by Karina Smigla-Bobinski written by Arnd Wesemann

21 Jul 2014

21 Jul 2014

Posted by admin

Posted by admin