Second Contact

by Société Réaliste

One of the most important characteristics of “territories” is that they are perpetually in flux. One should be able to document them simultaneously, but that makes their perception problematic. It is not possible for us to take a step back far enough to perceive their entire width or grasp the profundity of their depth. If we do move far back enough, we end up creating an observation post, which is a distinct territory separate from the one being observed. Here are a few concrete examples.

Take the beltway around Paris, the “Périphérique“, for example. A 35 km long urban speedway, the official purpose of which is to avoid traffic congestion. It is the second of the four-belt bypass system around the city: within Paris, the Maréchaux boulevards. Some hundred meters further out, the Périphérique; some ten kilometers further, the A86 highway; another 20, the Francilienne. All are designed for the same purpose.

The Périphérique is commonly seen as a psychological frontier, even though many “Parisian” infrastructures spread across it. It is clear that the system aimed at managing the flow that includes the Périphérique has a purpose beyond traffic control and the prevention of traffic congestion. This road is a fortification. In addition to this, there is the “pourtour de Paris”, a peculiar type of territorial moat. It is a strip of land that stretches around the outside of the Périphérique. Yet, it is not a part of the suburbs according to the cadastre. A “tiny” belt, some of it constructed, some of it empty. It is a buffer zone, in the sense that it helps distinguish one place from another and acts as a dividing line. As is the case of other buffer zones, this type of territory, even if empty, has a tendency to turn into a de facto wall, the point where the “sub” and the “urban” part. This zone allows for a certain type of flow, like a border control checkpoint, appointed not by the administration but by the mapping out of the city itself. It is a variable integration territory (VIT), just like there are variable message displays (VMD) all along the Périphérique. The fact that this zone is strategically kept as a fallow gives it a differentiating character (it creates a differentiation as much as it is a difference in itself and of itself). A difference under control.

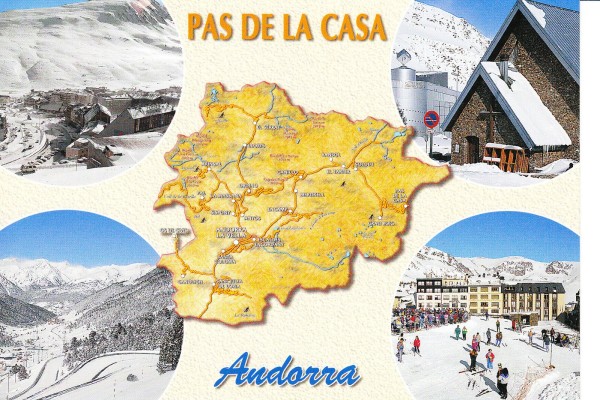

Then, there is that strange “city” called Pas de la Casa, whose territory belongs to the parish of Encamp, right at the frontier of the Principality of Andorra. It consists of buildings erected one meter behind the border control checkpoint. Why build a city there, in the middle of nowhere? There was nothing more than a shelter for shepherds in that area during the fifties because life in the middle of high mountains is not so easy. The Pas de la Casa was built in order to create a legal trench, a border city between France and the Principality of Andorra, a tax haven. There, poor people get duty-free cigarettes and rich people invest their money into special funds. Once the deadweight of the French and the Spanish laws was jettisoned over the Andorran mountains, it helped create the bricks that constructed the city walls. The territory is autonomous, but not entirely. It is a place where illegal trade becomes legal. But not just trade. It is also a land where smugglers operate under the benevolent eye of the officials in charge of public order, and where order organises and controls disorderly zones. Andorra, this tiny round country, functions as the legal blind spot of the French and Spanish periphery. It is an opaque mountain highway service area transformed into a state. A free trade zone, much like Hainan, used by two states that purportedly uphold the rule of law: France and Spain. This begs the question: if the rule of law does indeed have its place, does it not always need an area of lawlessness that is both peripheral and integrated, in order to exist? The more we look at Pas de la Casa, the more our perception of metropolitan suburbs changes. Controlled lawlessness.

There is also a country that nobody has heard of, which is nowhere near joining the EU, simply because nobody, apart from itself, recognises it. Well, not entirely – this country is called Transnistria and is recognised by Russia. It is a part of Moldova, which proclaimed itself an independent state in 1991; afraid it would become a Moldovan-Romanian province following the collapse of the Soviet empire. The territory is populated by 500 000 Transnistrians, financed and armed by the Russians, but not Russian. It is lawless area, recognised as such by the law. Yet another massive smugglers’ haven, another buffer zone, for sure. A territorial tool, but always under control.

What are these territories? “Fortifications”, if we understand this term by its Latin meaning “fortis facere”, or “to make strong”, “to strengthen” – something that happens to whoever controls them. Are they enclaves? Yes, but paradoxically, they are open. One finds them everywhere, at every level. At the state level, this depends on the point of view: there are five such “grey zones” according to the OECD and 43 according to ATTAC. But both organisations agree on the matter of Andorra. They also exist at the level of the road, at the building level, perhaps, and at the level of metaphoric territories.

We mentioned the Parisian “pourtour”, the Pas de la Casa and Transnistria, but we must also mention Tijuana and the Maquiladoras on the Mexico-United States border, the industrial parks by the Palestinian wall (which is considered to be a Security Fence, the “Jidar al-fasl al-‘unsuri”, the “wall of racial separation”), the two neighbourhoods in Karachi in North Nazimabad Town, called Buffer zone I and II, the square-kilometre-sized territory between Italy and Switzerland, Campione d’Italia, and the neighbourhoods in Havana where Westerners are allowed to partake in the “capitalism of the body”.

Within the complexity of the organisation of territories and the tangle of spheres, these are the areas of passage and separation. One must observe and inquire whether this is not indeed a checkpoint geostrategy. We can even provide it with a basic morphology: first area – checkpoint – zone – checkpoint – second area. Sufficient evidence must be provided in order to determine to which point the word “free” in the terms “free zone” and “free trade” pinpoints a central contemporary problem, repression through “freedom”.

We started off by saying that it is difficult to step back far enough in order to see the big picture, both in terms of width and depth. Société Réaliste’s project »Ministère de l’Architecture« is barely interested in architecture, and even less in ministries. However, it strives to bring together territories that have been unfortunately separated by geographic infamy. »Ministère de l’Architecture« strives to produce aberrant perceptions, which are nonetheless necessary. It should be thought of as a transit lounge in an airport, where entities that do not know each other gather and are provided with an opportunity to kill time together. What common ground is there between a parking area for trucks in Tiraspol, the bottom of the lake in Lugano, a wasteland in Porte d’Aubervilliers, a slum in Karachi, a bar in Mexicali, a hotel in Havana, a supermarket in Andorra, or a factory in Tulkarem? It is an exchange, which – although it is often unfruitful – could allow the peculiarity of these elements to disappear in order to illuminate some connecting threads. And then other checkpoints, other beltways, other grey areas will enter the picture. Proposals will be made, some will complain about the hyperactive incompetence of the Ministère, say that its officials are aloof, abusive and Byelorussian; people may even question what purpose stirring up these reflections serves; and the logo of the Ministère, erected, insensitive and dominating, will forward the question to all the duly documented territories.

What purpose can these areas serve? Why are we prevented from putting them in the same place? Is there a Transnistrian future for the Porte de Pantin? We must establish an intellectual tool in order to remove the term “nearshoring” from the economic vocabulary alone, and understand its urban, political and cultural meaning. If someone else were to talk about “grey zones with undefined contours, which both separate and connect the camps of masters and slaves”, could »Ministère de l’Architecture« help better pinpoint this vague definition?

Société Réaliste, Paris, July 2006

21 Jul 2014

21 Jul 2014

Posted by admin

Posted by admin